ソニーCSLが取り組む持続可能な新農法「協生農法」

農業により深刻化する環境破壊、生物多様性を守るために新農法を研究

――舩橋さんが取り組んでいる協生農法とは、どのようなものでしょうか。

舩橋: 食糧を生産するには、さまざまな方法があります。人類はまず狩猟、採集を行い、約1万2000年前に農業が始まったとされています。生態系の中にある食べられるものを集め、収穫するのが、食糧生産の基本的なやり方でしたが、農業は人間が管理した農地で計画的に食料を生産することができるようになりました。しかし、現在の農業では持続性に問題があることがわかっています。

一つは、資源の過剰利用です。肥料に使われる微量元素、肥料や農薬の製造工場で使われる化石燃料が枯渇することが懸念されています。もう一つは環境破壊。草原や森林を伐採して農地にするため、多くの動物や植物が生息地を奪われ絶滅する恐れがあります。工業生産も温室効果ガスの排出や大気・水質汚染などの問題を引き起こしますが、現代の人間活動において生き物を絶滅に追いやる最たる原因が農業なのです。

現在は、自然保護のために人間活動を後退させるか、人間活動を行うために自然を破壊しつづけるかというトレードオフの状態です。しかし、そうではなく、人間が増えるなら他の生き物も増やしてしまおう、両方増やせばいいじゃないかと発想を転換させたのが協生農法です。

――農業による自然破壊は、どこまで深刻化しているのでしょうか。現状を教えてください。

舩橋: 地球はこれまでに何度も大量絶滅の危機に脅かされてきました。実は現在、人間活動、特に農業によって地球史上6回目の大絶滅が起きると言われています。今のペースで人間活動を拡張しつづけると、数百年で地球上の生物の75%が絶滅するそうです。地球温暖化についてはよく議論されますが、それはCO2のような温室効果ガスは少数の物質的原因を特定しやすいからです。生物多様性の場合、絶滅する生物種の数だけターゲットがあり、その生存を支える要因も多様で社会生態系を横断する複雑な関係の上に成り立っているので、なかなか議論が進みません。

しかし、生物多様性が失われれば、我々が今まで恩恵を受けてきた生態系サービスが著しく損なわれます。例えば空気を浄化したり、水をろ過して飲用可能な状態にしたり、気候を制御したりということも生態系サービスに含まれます。端的に言えば、地球が砂漠のような状態になり、寒暖差も激しくなり、水は地表にとどまっていられないため大洪水か干ばつかの両極になることが予想されます。

――こうした未来を見据え、協生農法ではどのような取り組みを行っているのでしょうか。

舩橋: 普通の農業では1種類の作物を大事に育て、植えた苗がきちんと育って収穫できるように管理します。でも、それは植物の一つの個体に注目したやり方です。生態系では、さまざまな動物、植物が食物連鎖の中で関わりながらシステムが成り立っています。

例えば、人間の体は一つの個体で成り立っていますが、その中には約60兆個もの細胞がありますよね。細胞一つ取り出しても生き残るのは難しいですが、細胞が集まって一つの器官を成し、心臓、肺、皮膚などが組み合わさることで一つのシステムとして成立します。

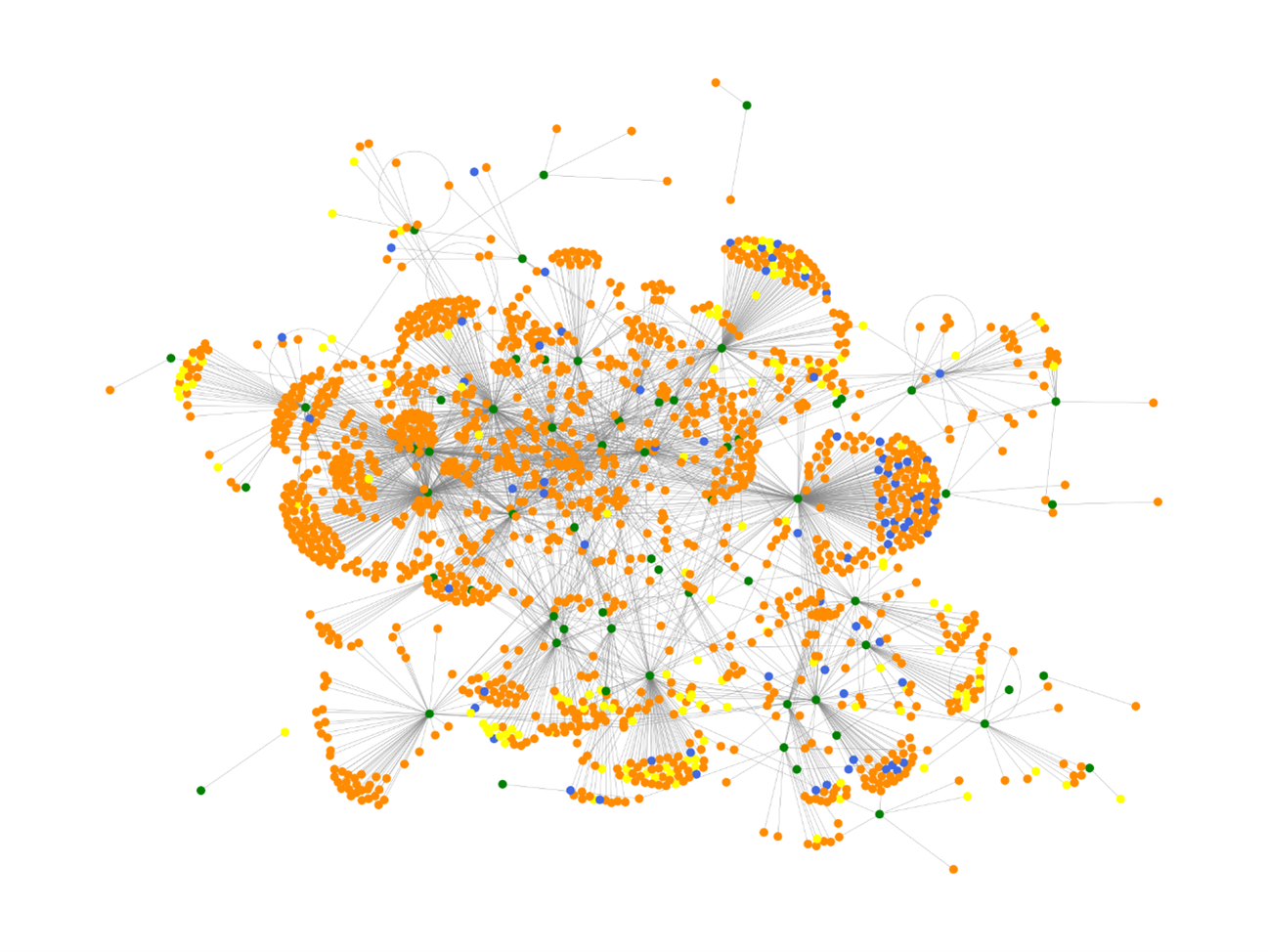

同様に、生態系も植物を1個体だけ取り出して生存させようとすると非常に手間がかかります。でも、食物連鎖の中で生態系全体の多様性を保つのはそれほど難しくありません。1個体の植物ではなく、作物、雑草、自然に生えてくる木、昆虫、動物も総合的に活用し、生態系全体で農業を再構築しようというのが協生農法です。これはソニーCSLが提唱する「オープンシステムサイエンス」にも通じるものがあります。

ソニーの情報処理技術を活用し、生物の生態系機能を情報化

――協生農法を行うにあたって、ソニーCSLを選んだのはなぜでしょうか。

舩橋: 数理科学系の博士論文を書いていた時に、そこに収まりきらない農業というテーマに行き当たったんです。社会的にも意義があり、10年後、20年後の自分が絶対後悔しないだろうと直感しました。個人的につながりのある研究所にも話を持ちかけましたが、コンセプトには賛同していただいても出資してプロジェクトを任せてくれる機関にはめぐりあえませんでした。

そんな時、偶然にもソニーCSLパリのオープンハウス(研究所公開)があったんです。そこで講演を聞き、みなさんが全力で研究に取り組む姿勢に感銘を受けました。これだけ全力かつ奇抜な研究所なら「農業を考え直す」というテーマも支援してもらえるのではないかと思い、当時所長だった所眞理雄さんに直談判したところ、ソニーCSLで研究できることになりました。

――ソニーCSLは、舩橋さんの研究にとってどのような環境ですか?

舩橋: 予想していた以上の幸運な出会いが、たくさんありました。日本のメーカーが農業に参入するとなれば、既存の農業にIT技術を使ったスマートアグリが一般的です。しかし、ソニーにはそういった縛りがまったくありませんでした。それに、ソニーグループのセンサー開発技術、情報処理技術は世界トップクラスです。協生農法で重要なのは、多様な生物が持つ生態系機能を情報化し、それをいかに組み合わせて使うかという情報処理の分野です。ソニーCSLは、それができるベストな環境だと思います。

――例えば、どのような面でメリットを感じていますか?

舩橋: 裁量権が非常に大きく与えられていることですね。私は東京に圃場を借り、約250㎡の中に1000種類ほどの品種を投入するという実験をしています。それを国や大学の予算でやろうとすると、実験以前に色んな正当化が必要なんです。しかしソニーCSLでは、すぐにアクションが取れる。もちろん失敗もしますが、それでも継続できるので、時間差でいろいろな成果が出てきます。そういった時間スケールを確保してくれるのが、うれしいところです。

わずか1年でアフリカ砂漠地域に植生を復元 驚きの成果を達成!

――現在は、日本だけでなく西アフリカの内陸国ブルキナファソで実証実験を行っているとお聞きしました。ブルキナファソを選んだのはなぜでしょう。

舩橋: 最初は、日本の農家とともに実験を重ねていました。その結果、日本のように降水量に恵まれて生物多様性が豊かな場所よりも、砂漠化の危機に瀕している場所でこそこのシステムは真価を発揮するという理論的予測が立ったのです。

今後地球上の生物多様性は減少し、砂漠に近い状況になっていきます。アフリカのサヘル地域(サハラ砂漠南縁部に広がる半乾燥地域)は、言わば明日の地球を象徴している場所。砂漠化の危機に最も瀕しており、経済水準も低いという、きわめて厳しい実験地と言えるでしょう。

そこで、アフリカの国々が集まるネットワーキングフォーラムで協生農法について発表したところ、現地のNGOが協力を申し出てくれ、1年間試してくれることになりました。

――どのような成果があったのでしょうか。

舩橋: 地面はカチカチで、種が飛んできても発芽しないような土地で、さまざまな農法と比較しつつ協生農法に取り組んでもらいました。すると、協生農法だけが異常に収量が高く、環境構築効果もあり得ないほど高いというデータが上がってきたんです。他の農法はすべて赤字でしたが、協生農法だが飛びぬけて黒字。500㎡という裏庭ほどの規模で実験しましたが、1年間でブルキナファソの平均国民所得の約20倍の売り上げが上がってしまったんです。これは普通の農業では決してあり得ない数字です。

慣行農業では収量を取り出したらその分砂漠化が進みますが、協生農法では砂漠状態から植生遷移を経て、最終的に小さなコケから草、ブッシュ、光を好む陽樹、その陽樹の陰で育つ陰樹といったすべての植生をわずか1年で定着させることに成功しました。一度砂漠化すると元の森林に戻るまでに大変な労力と年月がかかりますが、協生農法の場合、かつてない規模の食糧を生産しつつ、1年で植生を復元できたわけです。現地も大いに沸き立ち、ブルキナファソ政府の協力も取り付け、現地で大々的に協生農法を広めるという計画に着手しているところです。

|

|

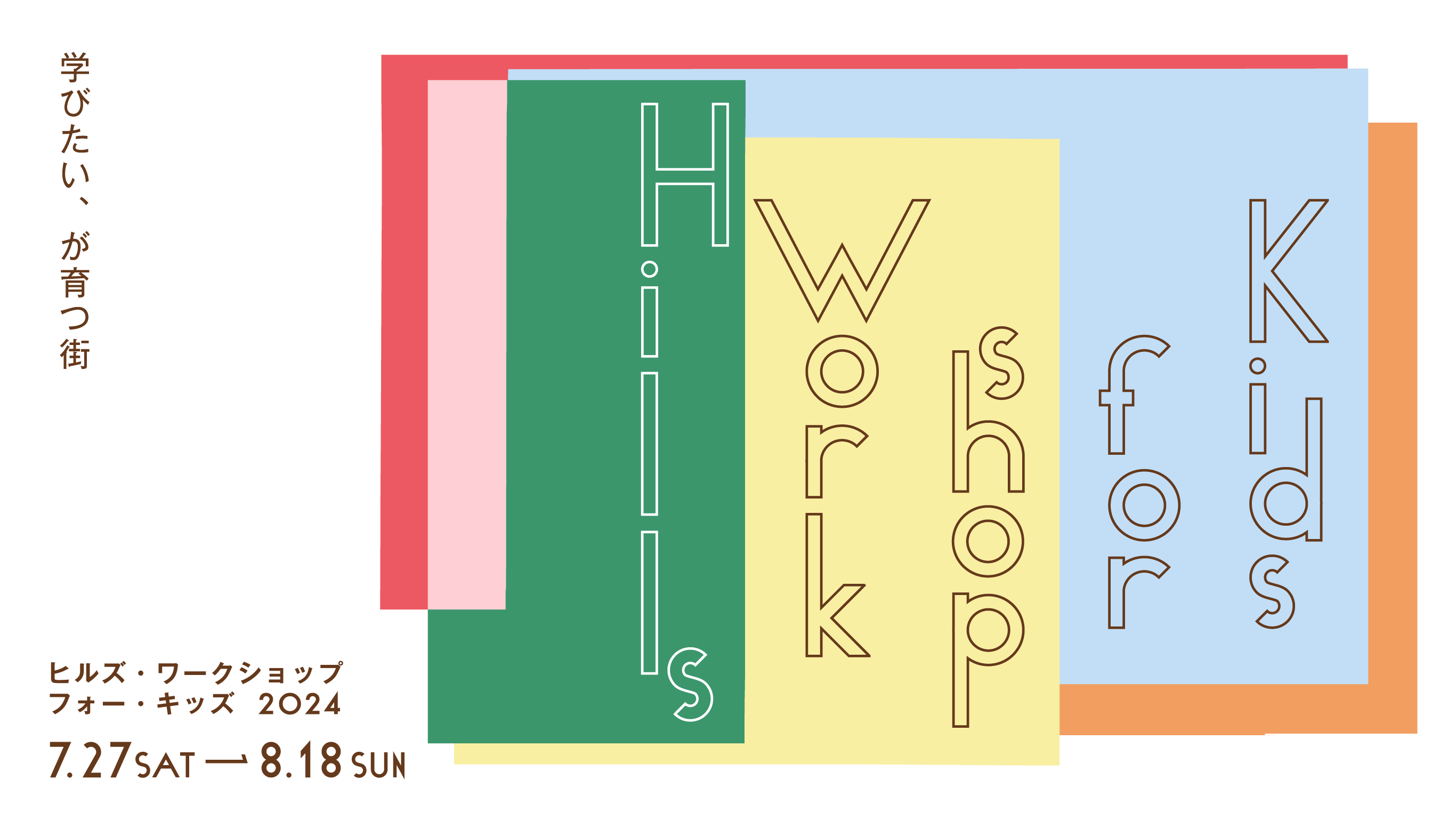

協生農法に取り組むブルキナファソの皆さん

――舩橋さんの予想どおりの結果と言えますか?

舩橋: 予想以上でした。メールで随時報告をもらっていましたが、収量の桁が一つふたつ違うのではないかと思ったほどです。もちろん理論的にはあり得ますが、現実が想像を追い越したような状況でした。細かいデータを提出してもらい、私も統計的な解析をしたりコストを計算したりと第三者的な立場で検証した結果、やはりこれは本当に有意なことが起きていると実感しました。

2020年の愛知目標(2010年に開催された第10回生物多様性条約締約国会議で合意された目標)には、持続可能な農業を2020年までに実現するという条項がありますが、おそらくどこの国も達成できない見込みです。しかしブルキナファソに限っては、協生農法をスケールアップすれば実現できるという試算が立っています。最貧国の一つで、自然環境も荒廃してるブルキナファソが、なぜか2020年に1国だけ愛知ターゲットを達成できるという、ゲームチェンジャーな展開が射程に入ってきている状況なんです。

もしかしたら、これまでの1万2000年という農業史の延長では決してあり得ない、まったく異なるもう一つの食糧生産システムが成立する可能性があります。その実証の第一歩が、アフリカのサヘル地域で成されたと考えています。

|

|

協生農法により緑を取り戻したブルキナファソの土地

――研究を進めるうえで、課題を感じていることはありますか?

舩橋: 理解を得るのが難しいですね。食糧生産は人間の生存本能に直結する問題なので、これまでのシステムを変えることに恐怖心を抱く方が多いんです。1万年以上続いてきた農業を変えることに、主観的な抵抗感があるように感じています。

これから10年、20年先、人口増加で生物多様性が減れば、今の農業が続けられなくなることは物質資源的にも環境負荷的にも明らかです。実際に危機に直面しない限り人々の意見は変わらないと思いますが、起きてからでは遅すぎます。いろいろな専門分野の間を橋渡ししつつ、新しいパラダイムを作っていかねばなりませんし、先行投資として研究するプロジェクトがいくつもあっていいと思っています。

ブルキナファソの場合は、国民が生きるか死ぬかの瀬戸際でした。「それが本当ならどんなに信じがたい話でも俺たちはやる、1%の可能性に賭ける」と言ってくれたから、計画を進めることができたのです。

ソニーCSLは機動性の高いマザーシップのような存在

――今後の展望についてお聞かせください。

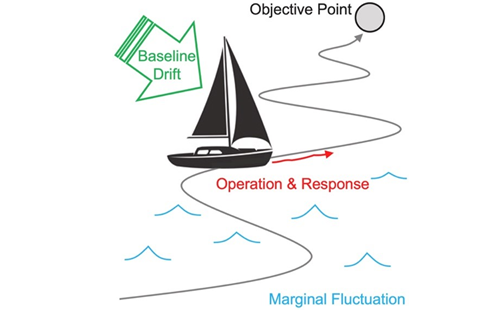

舩橋: いくつかの試験的な農場で成果が出てきたところなので、それを広く一般のスモールホルダー、家族経営規模の農家の方々にも使ってもらえるようなシステムを構築していきたいです。大規模なインフラではなく、スマートフォン一つあればデータを記録でき、「次にこういう植物種を植えたらいいのではないか」といった提案がくるようなものですね。そういったメガダイバーシティ(超多様性)をマネジメントするようなシステムを作り、オープンソースで提供することを考えています。その中で全球的にデータを集め、人間が増えてもその分他の生き物もきちんと増えるようにする。そういった地球規模で生物多様性が高い状態を実現していきたいです。

協生農法の研究は、何か具体的な要素技術を使ってイノベーションを起こすものではありません。グローバルに考えた時、地球の社会生態系を存続していくうえで最も苦しみが少ない状態は何かを考えた結果のデザインなんです。私たちは、食べ物や生活資源という形でさまざまな命を消費しています。それらはすべて生態系から取り出したものですから、消費を補って余りあるほどの生き物の命、生物多様性を作らない限り、私は自分の人生を正当化できないと思っています。さらに拡張して言えば、人類社会が地球上で持続していく価値があるとしたら、それは人類が存在したことによってこの地球上の生態系がより豊かになることだと思うんです。そんなことを考えつつ、研究を進めています。

――ソニーCSLでは協生農法に限らず、さまざまな研究を進めています。社会において、どのような役割を担っていると思いますか?

舩橋: 大きな事業を始める人たちは、少人数であり、必ずしもその分野の能力に秀でた人とは限りません。運や偶然にも助けられ、数人で新しいものを作っていきます。ライト兄弟が作った飛行機もそうですよね。当時は、誰もそれが現代の空輸手段、メジャーな交通手段になるとは思ってもみませんでした。でも、彼らは飛行機を作り、後に一大産業に発展したのです。

ソニーCSLは、そのような研究者を集めた小規模ながらも機動性の高い母艦のような存在だと思います。0を1にしたり、もしくは10まで育てたりする研究者を集め、さまざまな障がいから守ってくれる。これからますますその役割、機動性を高めていくと思います。それはアカデミアや経済活動にとどまらず、例えば私の考えるPeace Building(平和構築)の分野などにもさらに大きく広がっていくでしょう。政治情勢が不安定なサヘル地域で活動する中で、平和を作り出すのは農業を始めとする生活資源を作り出す人々であり、政治や軍事はそれを守る努力はできても直接作り出すことはできないということを学びました。そういった根本の活動を支えられるのは、実は個人や企業などの我々プライベートセクターの仕事であり、 プライベートセクターの科学者であるということが国連の会議などでポリシーメーカーと話すと必ず評価される点です。このような活動がもっと認知されれば、将来的にはいくつかの国の一次産業の情報基盤を支えるインフラを、ソニーCSLからスピンアウトした小企業が供給することもあり得るのではないでしょうか。

(2017/06/06)

# アフリカでの実証実験は AFIDRA (Association de Formation et d'Ingénierie du Développement Rural Autogéré) と CARFS (Centre Africain de Recherche et de Formation en Synécoculture) との共同プロジェクトです。

"Synecoculture" is a New Approach to Sustainable Agriculture from Sony CSL

Agriculture is accelerating environmental destruction; researching a new method of agriculture that preserves and restores biodiversity

――Dr. Funabashi, what exactly is "synecoculture"?

F: There are various ways to produce food. Humans were originally hunters and gatherers, but about 12,000 years ago, agriculture began. Collecting edible materials from the ecosystem was the foundation of food production, until humanity figured out how to farm, how to intentionally cultivate land and grow crops on it. We know, however, that today's methods of farming are not sustainable.

One problem is the overexploitation of resources. There are fears that the trace elements used in fertilizer, and the fossil fuels used in factories that make fertilizer and agrochemicals, will run out. Another problem is environmental destruction. Habitats are destroyed when grasslands and forests are cleared for farms, leading to the loss and potential extinction of many plant and animal species. Industrial production emits greenhouse gases, causes air and water pollution, and so on. Among all human activities today, it is agriculture that is the greatest driving force behind extinction.

Right now, we face a tradeoff between scaling back human activity to protect the natural world and destroying nature in order to pursue human activity. Synecoculture is a radical concept that rejects this tradeoff and proposes a way to support a growing human population while growing the populations of other organisms at the same time.

――How serious is environmental destruction from agriculture? Please explain how things stand now.

F: There have been a number of massive extinction events in the history of our planet. It has been said that the current wave of extinctions driven by human activity is the sixth largest in Earth's history. If human activity continues to expand at its current rate, 75% of the species on Earth could be wiped out within a few centuries. There is a great deal of discussion about global warming, but that is because it is easy to simply point to CO2 and other greenhouse gases as the physical cause of these issues. In the case of biodiversity, the target is purely the number of species going extinct. Because these species depend on widely varying factors to survive, and their numbers are based on complex relationships that cut across socio-ecological systems, it is difficult to get traction on discussing them.

However, when biodiversity is lost, we also lose the ecological services that provide us with benefits. For example, ecological services such as cleaning the air, filtering water so it is drinkable, and influencing the weather. In the worst-case scenario imaginable, the whole Earth becomes desertified, there are extreme temperature swings, and the water cycle becomes polarized between torrential flooding and droughts.

――How would synecoculture ward off a grim future like that?

F: In conventional agriculture, only one crop is focused on and carefully managed from seeding to harvest. This approach, however, focuses excessively on the individual plant. In reality, ecosystems are systems in which many animal and plant species are part of an integrated food chain.

For example, the human body constitutes a single organism, made up of 60 trillion cells. It is difficult to remove a single cell from the body and keep it alive, but cells gathered together form organs like the heart, lungs, skin, and so forth and combine into a single system.

In the same way, isolating a single plant from an ecosystem and cultivating it is very laborious. But if its place within a diverse ecosystem's food chain could be preserved, less effort would be required. Synecoculture is a reformulation of agriculture as an entire ecosystem. Instead of focusing on a single plant, it focuses on holistically harnessing crops, weeds, native trees, insects, and other animals. This is consistent with the Open Systems Science philosophy promoted by Sony CSL.

Using Sony information processing technology to digitally model the ecological functions of organisms

――Why did you choose to pursue the synecoculture concept at Sony CSL?

F: When I was writing my doctoral dissertation in mathematical sciences, I stumbled on a topic that seemed to be beyond the reach of those methods: agriculture. I sensed this was a topic of global importance, and that I would regret it 10 or 20 years down the road if I ignored it. I took my concept to a research lab where I had personal connections and it was well received, but no one was willing to actually fund the project.

Around that time, I happened to attend an Open House at Sony CSL Paris. I listened to the talks and was deeply impressed by the sense of total commitment to their research that everyone conveyed. I thought, just maybe, that I could receive support for my idea of transforming farming at this unconventional and extraordinary research institute. Mario Tokoro was the head of Sony CSL at the time, and I got in touch with him directly. The result was that Sony CSL took me and my research on.

――What kind of research environment do you find Sony CSL to be?

F: So many things about it make it an even more favorable fit than I had ever imagined. To the extent that Japanese manufacturers are involved in agriculture, it's usually so-called "smart agriculture," where IT is applied to conventional farming. But Sony is not involved in that side of the business at all. Additionally, Sony has world-class sensor and information processing R&D. The key to synecoculture is digital modeling of ecosystem functions composed of a wide range of organisms, and sifting through that modeling data to find optimal combinations. Sony CSL provides the best possible environment for an effort like that.

――What are some of the benefits you’ve noticed?

F: I am given tremendous discretion. I rented a 250-square meter field in Tokyo and planted about 1,000 different species in it as an experiment. If I had tried to do that under government or university funding, it would require all kinds of paperwork beforehand. But at Sony CSL, I could jump right into action. Of course, there are failures along the way, but I’ve never stopped pushing onward, and eventually my projects resulted in many successes. I'm delighted by how Sony CSL gives me the freedom to work on my own schedule and allows me ample time to produce results.

An astonishing achievement: restoring vegetation to a desertified region of Africa in just one year!

――I've heard that you are currently doing field experiments in Burkina Faso, in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in Japan. Why did you choose Burkina Faso?

F: Initially, I conducted experiments with Japanese farmers. Those results yielded theoretical predictions that this system would actually prove more valuable in places threatened by aridification than in places like Japan with ample rainfall and high biodiversity.

With Earth's biodiversity decreasing over time, we are headed toward becoming essentially a desert planet. The Sahel region of Africa (the semi-arid belt on the southern fringe of the Sahara Desert) is considered a harbinger of tomorrow's planet Earth. It is a very unforgiving environment for a trial of synecoculture: highly susceptible to aridification, and afflicted by extreme poverty.

At a networking forum that draws participants from across Africa, I made a presentation about synecoculture, which prompted a local NGO to offer its cooperation in a one-year trial.

――What were the results of that trial?

F: The soil was so dry and cracked that if you scattered seeds on it, they would not sprout. We implemented synecoculture alongside other farming methods for comparison. The data showed that only synecoculture yielded remarkably plentiful harvests, while also providing amazingly positive environmental effects. All the plots using other farming methods were in the red, but the synecoculture plot was far in the black. The plot was about 500 square meters, only about the size of a backyard, but the value of its produce was 20 times higher than the Gross National Income per capita of Burkina Faso. No conventional method of farming could have given those results.

Traditional agriculture leads to progressive desertification after harvesting, but synecoculture succeeded in establishing, via designed plantings, a transition from desert conditions to a blend of mosses, grasses, bushes, sunlight-tolerant trees, and shade-loving understory trees within a single year. Although it usually requires massive amounts of effort and time to restore vegetation to land once it has desertified, synecoculture allows the restoration of plants in just one year while also producing an unprecedented amount of food. There is now enormous interest and the Burkina Faso government is working with us on a plan to conduct large-scale synecoculture trials.

|

|

Synecoculture participants in Burkina Faso

――Would you say the results met your expectations?

F: They exceeded my expectations. I received regular updates via email, and I thought that the numbers I was seeing must be in error by a decimal place or two. Even though I had the theory to suggest that it was plausible, it surpassed what I imagined to be realistic. When I obtained the granular data and performed statistical analysis, cost analysis, and so on in order to validate the results objectively, I realized that I had something really significant on my hands.

The 2010 Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity included a provision aiming to implement sustainable agriculture by 2020. At present, it does not appear that any country will meet that goal, known as Aichi Biodiversity Targets. But if we can scale up synecoculture in Burkina Faso, it could be the only country to make it, according to my calculations. If one of the world's poorest countries, facing some of the world's worst environmental crises, could be the one country to hit the target of that convention provision, it would be a complete game-changer.

It’s possible, after 12,000 long years of agricultural history, for an entirely new food production system to be established. The first step toward demonstrating that is now unfolding in the Sahel, in the heart of Africa.

|

|

Land in Burkina Faso revitalized through synecoculture

――What challenges do you foresee as you move forward with this research?

F: It's hard for people to understand synecoculture. Because food production is directly tied to the human survival instinct, there is widespread fear about changing our existing systems. There is a subjective reluctance to change how we have been farming for more than 10,000 years.

Ten or 20 years in the future, if population growth leads to decreased biodiversity, it's clear from a resource and environmental perspective that today's form of agriculture cannot continue. People don't change their minds until a crisis is staring them in the face, and then it's too late. We need to bridge multiple academic disciplines to create a new paradigm. I believe there are multiple research projects that are worthy of precautionary investments.

For Burkina Faso, they’re at the brink of a life-or-death situation. People there have said to me, "No matter how hard it is to believe synecoculture can do all that, if there's even a 1% chance, we'll take it." That's why my plans have been able to move forward there.

Sony CSL: A highly maneuverable mothership

――What prospects do you see ahead?

F: Because we have results from multiple test farms, I now want to design a system that can be rolled out to ordinary smallholder farms and subsistence family farms. They are the vast majority of world agriculture. No need for big infrastructure, just a smartphone to record data and offer suggestions like "Next you should plant so-and-so plant in such-and-such a way." I'm thinking of developing an open-source software system for such "megadiversity" management. It will gather data from all around the globe and make it possible for the population of other species to grow, instead of shrink, as the human population grows. I want to sustain high levels of biodiversity on a global scale.

Synecoculture research is not about creating innovation using specific technological elements. It's designed from the perspective of considering socio-ecological systems that could minimize the ruthless loss of all living species as little as possible on a global scale. We consume the lives of many living things in order to eat and obtain basic necessities. All those lives come out of ecosystems, so I believe that I cannot justify my own existence if I fail to replenish biodiversity as compensation for my own consumption. To speak more broadly, if there is value in human civilization continuing on this planet, it comes from humanity enriching the biodiversity of the planet through our existence. That is the philosophy that drives my research.

――At Sony CSL, research is not just limited to synecoculture. What do you think other research contributes to society?

F: When a few people start a big project, they may not necessarily have the foremost expertise in that field. With a little luck, a small number of people can create something new. The Wright Brothers' airplane is an example of that. At that time, no one imagined that someday air travel would become a major means of transport. But they built a working airplane and kick-started an enormous industry.

Sony CSL is like a small but highly maneuverable mothership for researchers who have the spirit of the Wright Brothers. It gathers researchers who start something from zero and they may take one step forward, maybe even going from "0 to 10." It shields them from obstacles. I think Sony CSL will have even more mobility in the years ahead. For example, it will expand its reach beyond academia and business into fields such as what I call "peace building." Working in the Sahel where there is much political instability, I learned that the people who build peace there are those who build resources providing livelihoods, starting with farming. The government and the military can do their best to protect livelihoods, but they can't directly create them. In actuality, it's the job of the private sector to support those basic livelihoods. When I talk to policymakers at events like UN conferences, they always appreciate that I am a scientist representing the private sector. If enough awareness is raised of the work we are doing in this area, perhaps it may even be possible for Sony CSL to spin out a small company to supply the digital infrastructure that is essential for primary producers in many countries.

(2017/06/06)

# Field experiment in Africa is a joint project with AFIDRA (Association de Formation et d'Ingénierie du Développement Rural Autogéré) and CARFS (Centre Africain de Recherche et de Formation en Synécoculture).